I first read The Summer Book by Tove Jansson about five or six years ago. It is a delightful story centred around an elderly artist and her grandmother who are holidaying on a Finnish island. I occasionally reread it throughout the seasons and especially in winter, when I am wishing for summer.

I recently tuned into the live screening of “Haru, Island of the Solitary”, hosted on Youtube by The Moomins Official channel. They said it would be a ‘this hour, only’ event and it’s true – you can’t watch it anywhere.

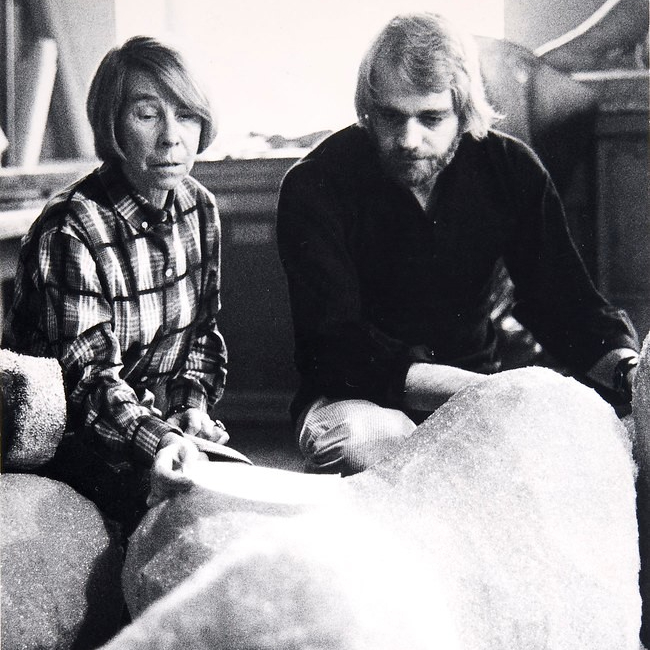

The documentary was filmed by Tove Jansson’s partner, Tuulikki Pietilä – here is a photograph of them together on Klovharu in Finland. Tove is clearly the muse in this documentary: Tove building the log store, Tove dancing with their cat (the cat is a firm feature) or watching the sky on the eve of a storm. There is a beautiful scene where Tove dances to San Francisco by Scott McKenzie, casting shadows on the curtain (you can see a small snippet from this section of the doc here, starting from 1:10).

A Microscopic View

The entire documentary has a psychedelic vibe to it and it’s certainly of its time. What I loved most in this documentary was the level of detail. Every quotidian detail is brought into sharp focus. This is done not with the filming technique particularly (probably due to limitations of technology at the time?), but with Tove’s delicate prose. Every sentence in this documentary carries weight and none could be removed without losing something important.

In one shot, the couple are blowing bubbles outside. They start by watching lots of bubbles float by together. Finally they focus on just one bubble, watching it drift slowly out to sea. Everything is slow and hypnotic. Tooki (Tove’s nickname for her partner) likes to watch the clouds – she says they remind her of the sea, because they are always in motion.

They spend afternoons fishing in ‘absolute silence’ , relishing the solitude. Tove describes in detail a beautiful rosebush she has found springing out of the log store. They collect the wood for the store from the beach as it floats in from other islands. Tove talks about these activities as a typical day, saying this is their ‘work, play and ritual’.

But not everything feels light and easy. One night, they spot a boat struggling in the storm and the next morning it is clear there are no survivors. Afterwards they don’t discuss it – it is something that can’t be touched.

The Reviled Gull: As Bad as They Seem?

Gulls, or ‘sea gulls’ as they are more commonly known by us city folk, rarely emerge as the heroes of any story (especially in that story in The Sun –I wouldn’t take it personally if I were them).

That is why I was so pleased when Tove and Tooki befriended a gull. They named her Pellura. At one point, Pellura ‘snatched a salmon sandwich from Tooki’, but they hold no ill will towards Pellura and her visits continue.

It reminded me of a gull drama etched in my own memory. When I was about seven years old, I had a baby doll named Rebecca. I took her everywhere. My mum, Rebecca and I were sitting on a wall in Oban one summer, when a local gull swooped in to steal our tuna sandwiches. Without hesitation, my mum grabbed Rebecca by the leg and swung her at the gull several times. I was more worried about my doll falling to her death in the sea than the loss of my lunch.

I had a negative view of them for years after that. It took me ages to appreciate the fact they are just another living creature trying to get by. They are also excellent co parents. Last year, a closely guarded baby left the nest and spent about two weeks sleeping and practicing flying on the ground behind my flat. I put up a note on the back door, warning the dog and cat owners who often left their animals out the back. A week later, the bird spread its wings and flew away.

Ageing on Haru

As time passes, Tove finds she has to build sets of steps to places that she had reached easily for years. Tove and Tooki have to face the fact they are ageing. Tove admits that she ‘began to fear the sea’ and it troubled her. For her, the waves no longer represented adventure, but danger. She felt this fear was a betrayal of who she had always been.

Feeling they have no choice, they pack and close up the house. It was time to return to civilisation. Before leaving, they fly a kite together. The wind blows it far, far away, off the Gulf of Finland. It made me think about what Tove said before about their daily rituals. This was a goodbye ritual and it doesn’t matter where you go in the world – humans need rituals, to make sense of themselves and their place in the world.

What I loved most about ‘Haru, Island of the Solitary’ was the microscopic view I mentioned earlier – the island became a living, breathing entity in this documentary. It had its own heartbeat, its own desires and dreams.

I don’t think I have seen this point of view covered before. In every other narrative I have read about islands so far, things happen to the island and no one is thinking too closely about what the island might want or need. I think if we appreciated nature as its own entity in this way, we might think twice about how we treat it. Last year, the Whanganui River in New Zealand was granted the same legal personhood as a human. I think this is a theme that is going to become more and more prominent in the coming years.

The documentary has made me think differently about how I regard islands. After the hour had finished, I felt restored – as though I too had just come back from a trip to Haru.

“Sometimes it was as if one had fallen hopelessly in love: everything seems out of proportion. I felt, for example, that this extremely spoilt and mistreated island was a living creature. It disliked us or pitied us, depending on how we behaved or on the island’s own mood”.

Tove Jansson: Haru – An Island (WSOY 1996)